For a while I wondered why Google wanted me to sign in. Now I wonder why I ever would. If you have Gmail and a personal YouTube account that simply must store what you watch and recommend new things and broadcast your choices hither and yon, and you use Google calendar and Google Plus and Google Clear and Google Bold (now with chipotle) and Google Whitening Google with Deep-cleansing Foaming Action, then I suppose it’s necessary to stay signed in.

But then there’s this:

Google announces privacy changes across products; users can’t opt out

That’s the sort of headline I take to mean “tech company does something, reporter not quite clear on details but it seems bad.” But we read on:

The Web giant announced Tuesday that it plans to follow the activities of users across nearly all of its ubiquitous sites, including YouTube, Gmail and its leading search engine.

Consumers won’t be able to opt out of the changes, which take effect March 1.

The move will help Google better tailor its ads to people’s tastes. If someone watches an NBA clip online and lives in Washington, the firm could advertise Washington Wizards tickets in that person’s Gmail account.

(snip) But consumer advocates say the new policy might upset people who never expected their information would be shared across so many different Web sites.

A user signing up for Gmail, for instance, might never have imagined that the content of his or her messages could affect the experience on seemingly unrelated Web sites such as YouTube.

I suppose there are two responses: 1) everything is already tracked / you have no privacy / we are all inmates in a Panopticon who willingly entered our cells, and 2) no big deal, it’s just machines customizing helpful suggestions. But any company with the heft of Google ought to know the danger in issuing a new strategy whose description can contain the phrases “changes to privacy settings” and “cannot opt out.” No! Come here! We want you to get a good deal on tickets. You would be wrong not to want to get a good deal on tickets. What’s the matter? You don’t want the tickets? WHY DON’T YOU WANT THE TICKETS?"

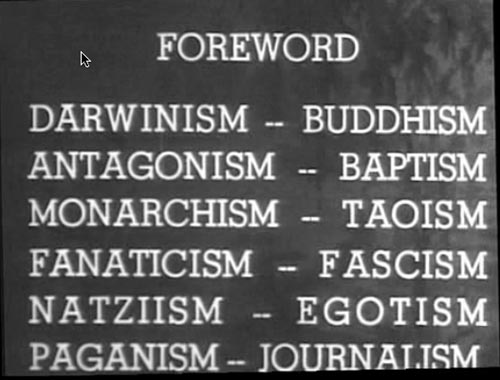

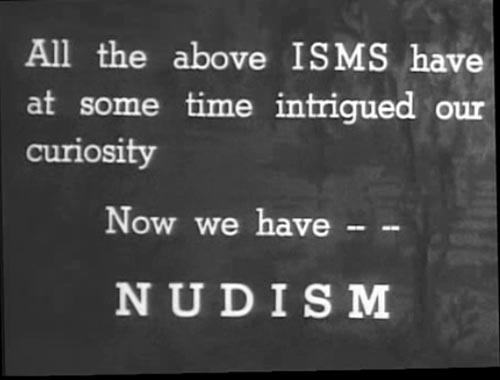

Silly me; there was more to those Nudist credits. In the interests of completeness, then - and we are always interested in completeness - here you go.

Actually, I am not interested in completeness. Just enoughness. I see people at the postcard shows with the complete run of this or that, collections that have been assembled from a hundred sources until they have every single one of the 65 hold-up-to-the-light linen ad cards from 1897. Impressive. And now? Aw, I don’t know, make me an offer.

Completeness is useful for context, but I suspect context is one of those impedances we’ll cast off entirely. It’s a bother. It’s easier to view everything through our own standard, and disassociating things from their context makes the past just a big fun junk store full of stuff we can remix. So you get a culture whose entire diet is seed corn.

Anyway. “Completeness” requires scanning everything in a magazine and keeping it together so we see it all, but I don’t. I keep the originals. You can hold the magazine in your hands and page through it; the thing has weight and a scent; it’s physical. The individual pages scanned and put in a folder are just sequential images. Look at “Life” magazine on Google, and it’s the same - they’re freeze-dried versions of the real thing. But at least they exist as contiguous entities, not chopped up and scattered around the web as “Vintage” pictures that make us feel good about our current social mores and uneasy about current notions of adult behavior. (Everyone looks much more grown up in the 40s and 50s.) Bur our satisfaction about the former always makes the latter easier to take.

On a somewhat related note: there’s a phrase on the internet I see a dozen times a day: “that awkward moment when.” What a perfect term for people who grew up on the internet, and find the real world full of unsettling examples of human interaction. Conflict of any sort is awkward, unless it's Harry Potter stuff or a few frames from LotR, and then it's awesome, but generally, anything that intrudes on the isolation of the individual is awkward - partly because it may remind everyone that the community of the web is illusionary, and consists mostly of shared references and the ability to decode the hieroglyphics of rage comics. It's part of being young, I suppose, but I feel sorry for kids whose current culture is only the internet in its popular passed-around form, with its constant reminders of how awesome it was to grow up in the 90s and like Pokemon and Star Wars.

One of the few boons growing up in the 70s was the brief Nostalgia Boom: for a while people were very interested in the 30s, perhaps to find a time in recent memory that was worse, and then they were besotted by the imaginary "Happy Days" period, which stretched from 1955 to the second week of November, 1962. It may have been fantasy, but we grew up with a sense that our culture had been preceded by another.

Yawn. I'm bored with everything I say today.

Today: “The Magnificent Ambersons” in Black & White World. As a fan of Welles, I was curious to see what this wreck was like. Even if the story was hacked up and a happy ending tacked on the back, surely it would look great. Well: I was surprised. Visually, it’s a mess. Earlier in the evening I’d started a movie called . . .

. . . and it was a dull, talky affair. But I kept trying to place this guy:

I’m sure you’ve had the feeling: you can see the guy in another role, but you can’t place it. Imdb helped eventually, once I googled all the actors, and finally, ah-ha. He was the studio exec in “Singin’ in the Rain.” Died the year after. He has one of the greatest moments in musical history, one that comments on the underlying silliness of those elaborate productions supposedly set on a stage. Gene Kelly describes the “Broadway Melody” sequence, which is the high point of the movie; by the time we get back to the room where he’s making the pitch, we’ve forgotten he was just describing what he wanted to do. “Nope, can’t see it,” says the studio exec, and the idea is dropped and never mentioned again. Always thought that was hilarious. Anyway.

And then there’s the leading lady, one of those brittle, self-important, nasty women who usually ended up dead in a movie like this. A beaut:

Patricia Dane. Her imdb page says:

Admired by fellow actors after she brusquely told off an MGM studio executive. Changed name to Pat after this incident but only starred in minor roles and bit parts after 1945.

Hmm. Doesn’t that make you want to know more, perhaps? She was born Thelma Pearl Pippins, married Tommy Dorsey, tried to restart the career after the inevitable divorce, but memories are long in Hollywood, and she didn’t get anything. Her work in this movie may have been instrumental; she’s just a pill, as my mother used to say about unpleasant people.

Finally, a look at the control room of Grand Central Station, as imagined by a set designer with a budget of $42.78:

There’s something missing in the film, and it’s “Grand Central Station.” Pity.

Anyway: Ambersons! See you around.