The size of your house says little about you; the reasons for the size are another matter. (Assuming you chose the size, instead of having it dictated from economic circumstances, of course.) Some people like cozy dwellings; some people want room and land, spreadin’ out so far and wide; others want to be stacked in a hive with a commanding view. And so on. Wanting distance from others doesn’t make you anti-social, any more than wanting to live in a small flat in a large building makes you gregarious. It’s all part of who you are and how you want to be seen, with the mixture of the two depending, again, on the individual.

So. When a guy decides to live in a Dumpster, you can make some assumptions: he has freed himself from the tyranny of possessions, has an instinctive need for the close quarters of an animal’s den, and has no problem voiding his bladder and bowels in a bucket. The professor in this story lives in a rehabbed Dumpste. He has an office with running water and plumbing, so it’s not as much of a sacrifice as you might expect.

Why he does it at all doesn’t interest me in the least. He doesn’t have to. He wants to. If he was doing it to space-shame people in the Tiny House movement, it would be amusing; no matter how pure your objectives, there’s always someone purer to accuse you of being a sell-out. It would be funny if he took issue with the Tiny House people for clinging to bourgeoise notions of individual space and unsustainable materials; those houses must be made from things, after all, and Dumpsters already exist, just waiting to be reclaimed. (And, you assume, power-washed.) But it’s a project to raise awareness about sustainability. College students assist him with his Research.

It’s the subhead of the Atlantic article that irked:

One professor left his home for a 36-square-foot open-air box, and he is happier for it. How much does a person really need?

The question of how much space do we really need suggests there is a standard, a one-size-fits-all answer, and that finding out how much “we” need will cause us to change the way we think about housing. It’s a question better asked of enormous houses built as showplaces for one’s monetary accomplishments, or to house a huge brood, but even then it’s none of your business. (I’ll leave aside such things as mortgage deductions, because some people believe that a tax deduction = a direct transfer payment from the government, and that the public coffers are lessened because you have been taxed at a lower rate. This is the line of thinking that says it’s not your money in the first place, but that’s another matter.) Obviously many houses are bigger than people need. So? I don’t need a dog. I don’t need a child. No one needs a TV or a washing machine.

The last person to tell anyone how much space they need is the person who sleeps in a metal box previously used to store garbage between weekly pickups. But:

For Professor Dumpster, the undertaking is at once grand and diminutive, selfless and introspective, silly and gravely important, even dark. “We bring everything into the home these days,” Wilson said. “You don’t really need to leave the home for anything, even grocery shopping, anymore. What’s interesting about this is it’s really testing the limits of what you need in a home.”

This is incoherent. “We bring everything into the home these days.” Except for the things we don’t. And even if we bring things into the home . . . so? “You don’t really need to leave the home for anything, even grocery shopping, anymore.” Again with the need. If there’s enough scolds telling you what you don’t need, what you actually want becomes an anti-social act, I suppose. And yes, I want to leave the home for grocery shopping sometimes, because the act of wandering around the store, assembling what you need for the evening meal, seeing what’s new, seeing other people, talking to the clerk - it’s called “getting out of the house,” and when your house is three square yards I would think that would be appealing. “What’s interesting about this is it’s really testing the limits of what you need in a home.”

Because the basics are a complete surprise to most people. Turns out a floor, walls, a roof, some water, and a little electricity for luxurie - that’s it! That’s all you need. And a baby monkey only really needs a felt-covered wire model of a mother with milk coming out of a hole.

“The big hypothesis we’re trying to test here is, can you have a pretty darn good life on much, much less?” He paused. “This is obviously an outlier experiment. But so far, I have, I’d say. A better life than I had before.”

Again: if he’s happy, I’m happy. But he sounds as if he has a pretty darn good life because he has tenure, a job, a calling, and a social circle; take all that away and I imagine that living in a steel box is insufficient to make one’s life better. But if it’s better for him than I wish him luck, and hope we leave it at that.

But they aren’t leaving it at that.

“What does home look like in a world of 10 billion people?” the project’s site implores, referring to the projected 40 percent increase in the human population by the end of the century. “How do we equip current and future generations with the tools they need for sustainable living practices?”

Unfortunately the site does not answer those questions in concrete terms. But with only 39 percent of Americans identifying as “believers” in global warming, just raising questions and promoting consciousness of sustainability might be a lofty enough aspiration.

Holy irrelevant whiplash, Batman. First of all, if they’re doing this project because of global warming, perhaps a future of putting people into metal crates isn’t the obvious solution it might appear.

Second: the next few billion don’t want to live in a Dumpster. They want to live in a nice place in a safe neighborhood that doesn’t have an estuary of offal flowing out the front door. There might be lessons gained by turning a Dumpster into a multi-level solar-powered dwelling (that’s the plan, according to the article; apparently the Dumpster is not enough, and he needs more) but unless the problem facing the slums of Brazil is an excess of steel containers in need of retrofitting, it seems you’d be better off designing something useful. Like inexpensive pre-fab modular housing with enough variations so people feel as though their dwelling has some individuality.

(Always amusing how the lyrical snipe at the suburbs - “ticky tacky houses, all alike” - doesn’t seem to take into account the lack of visual diversity in a big-city housing high rises from the same era, with their blank walls perforated by 30 floors of identical windows.)

There’s another objective here, however: Environmental Justice.

I don’t trust any sort of Justice that needs to be modified, because it is arbitrary, subjective, not codified or subject to appeal, and assumes a prima facie good that trumps objections. If you object to a goal of Environmental Justice you are doubly damned, once for hating the Environment, and once for being Unjust. Compare two mission statements I just made up:

“We are committed to providing inexpensive, durable, sustainable housing to urban communities where the majority of impoverished people life in make-shift, unsanitary conditions.”

“We are committed to Environmental Justice in housing, both at home and abroad.”

Which one is involved in making, and which one is more likely to include Taking as part of its mission? The latter type of Justice usually means making something, yes, but I’d bet it also involves an Environmental Justice Levy on houses larger than the EJ League approves of, and puts limits on homes constructed in the future. Urban planners made it possible for people to leave the city for detached houses back in the 50s and 60s, and by God we’re not going to let that happen again.

(Note: in one of the suburbs I drive through now and then, whole blocks are being remade. New owners tear down the old small houses, with their tiny kitchens and small living spaces, and construct new dwellings that are often twice the size. The architecture is usually better; the houses amplify a historical bungalow vocabulary without making it seem overdone or trendy. All the houses fit; all look different. The tax base is increased. This is generally regarded with horror by outside observers, because it’s driving out the smaller houses. You know. The Ticky-Tacky Ones.)

At this point in my ramblings I thought I should google Environmental Justice, and what pops up but an EPA page. Turns out we just had the 20th anniversary of a 1994 Executive Order about EJ. There’s an EPA Office of Environmental Justice, which no doubt takes advice from the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council. (“The Council provides advice and recommendations about broad, cross-cutting issues related to environmental justice, from all stakeholders involved in the environmental justice dialogue.”)

None of it has anything to do with housing, but once you’ve asserted that every tangential issue - zoning to transportation to expanding the taxing authority to leap across city borders to redress historical inequalities to mandating density - cannot be separated from Environmental Justice, you’ve managed to shut up a whole big swath of people who suddenly find themselves Unjust, and don’t like it at all, and are eager for absolution. They will often find it at the home of a very rich person with a big house by the lakes holding a fundraiser for the proper candidate.

It’s not about what people want. It’s what about they should realize they don’t really need, and if they can’t understand that on their own, well, removing their options is one way to get the point across.

The fact that one guy is satisfied living in a bin without a toilet doesn’t mean that there’s a lesson for the rest of us, any more than someone with an amputation fetish makes us realize we don’t really need ten fingers. But that’s how it goes. Writers who championed all this cool “You’re Living Your Life Wrong” stuff when they were in college find themselves in their early 30s writing “In Defense of the Pinky Finger,” thinking man, I’ve really turned into my parents.

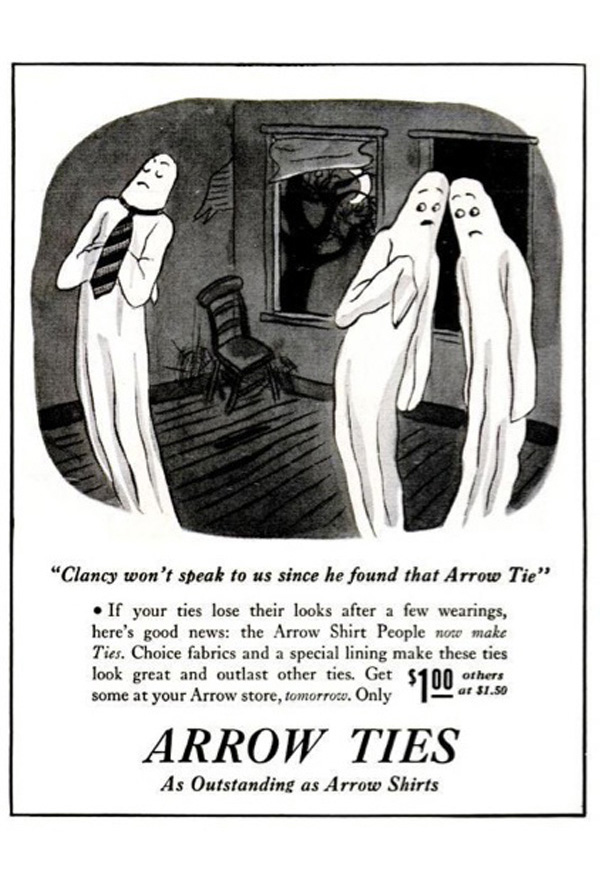

We are Bordenless this week. That'll happen. But we have cliched dead people in ectoplasmic form:

Looks like a Charles Addams, but it would be signed if it was. Typical spook house - busted chair cracked plaster, lousy shade. But why are they wearing sheets in the first place? An old tradition. Burial shrouds.

The real question is why Clancy looks so arrogant, or angry. Just because he has a tie. Does this mean flesh-and-blood people will turn insufferable as well?

DRINK BEER FOR MORE LIFE

The simple things in life - although the man's expression of rueful, humorless amusement suggests that the beer won't be enough.

Wikipedia:

The beer was locally popular in Detroit from the company's inception, but grew in popularity and was eventually available in many states for a brief period in the 1940s, with an ad campaign in Life magazine that featured restaurant ads from many famous eateries around the country using Goebel beer as an ingredient.

It was brewed in Detroit from 1873 to 1964, after which it was sold to Stroh's. It had a spike in the 70s and 80s, because it was cheap. Pabst bought it. Pabst killed in 2005.

Behold: a gallery of cans over the years.

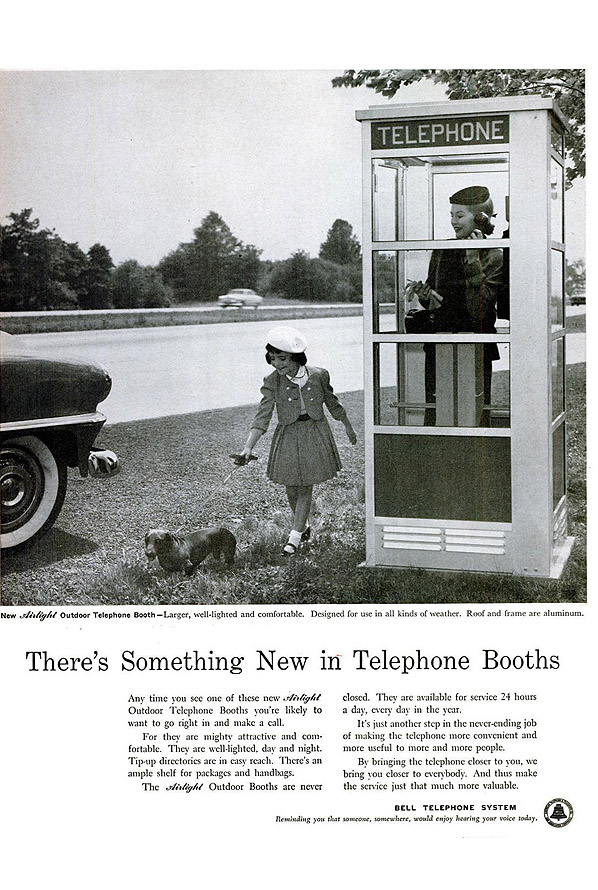

IT HAS A NAME

These were everywhere. Now they are going away.

The Airlight!

SO . . . .WHY?

One must ask what the point was, then.

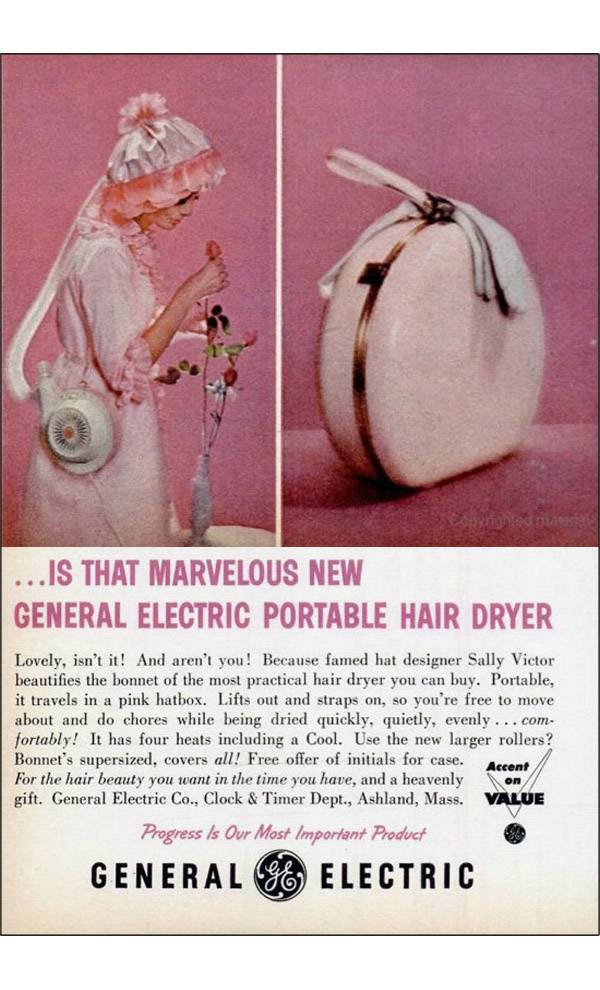

SALLY VICTOR DESIGNED IT

Another piece of 60s design that could be called iconic, and probably should be, except that I hate the term. It's overused. But these were stylish machines.

My mom had one. I remember how it smelled. Anyway, Sally:

Victor aspirations were simple and pure; she believed women loved pretty things and liked to be noticed wearing them. Although she was occasionally denigrated for her pursuits, like when Eugenia Sheppard of the New York Herald Tribune (25 March 1964) said Victor was "sometimes accused of designing too pretty, too feminine, too becoming, too matronly hats," Victor was credited for reviving the Ecuadorean economy by making the Panama straw hat popular again, even with the young women of the mid-1960s.

I read a piece recently about how Ecuador wants to reclaim the reputation for Panama hats. They're making fewer and fewer these days - Chinese competition, as you might expect. Fewer thana dozen weavers can make the "Montecristi"

hat. But:

The art of weaving the traditional Ecuadorian toquilla hat was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists on 6 December 2012.

So they got that going for them, which is nice.

Finally:

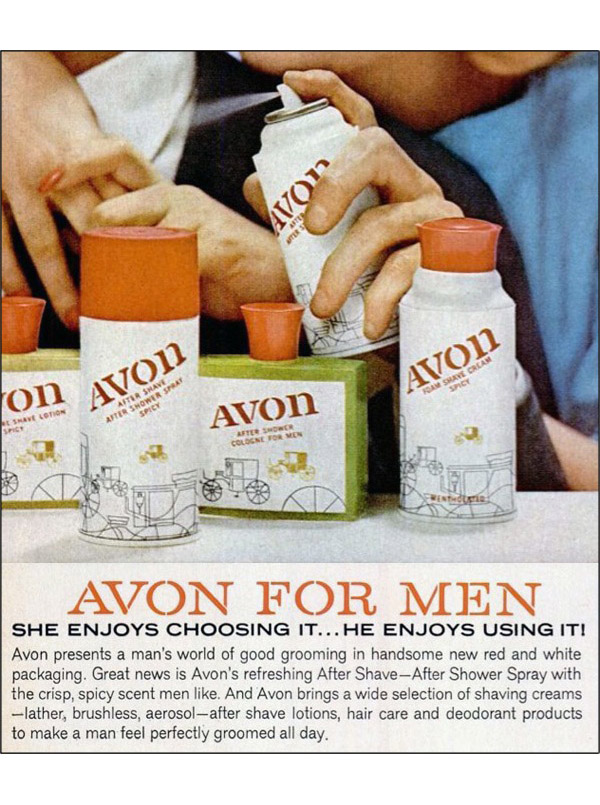

MANLY YES, BUT HE LIKES IT TOO

It's a man's world in the Avon Grooming line:

This caught my eye for the design - not so much the stenciled letters, which were a cliche of the time, but the old-timey conveyances as a sign of Manliness, and the way they're arrayed. If you're my age or thereabouts, it's the sort of thing you saw in your dad's part of the bathroom - year after year. Never used.

Reserved, perhaps, for a special day.

|